Here’s one that’s bound to bring a nervous smile to almost any soldier’s face. You remember it because it hurt. You smile because there’s nothing you can do about it.

What is it?

It’s the memory of a hot, spent casing from almost any weapon on bare skin. How many of you can recall the inrush of air as the metal seared your skin? Some of us cursed. Or cringing, knowing it was going to hurt.

For me, I got to feel that during AIT. We were practicing doing patrols, and we had the old jeep with an M-60 machine gun mounted on a stand. One thing you practice is getting out of an ambush zone. We call this a kill zone, and that’s exactly what it is. You’re in it, you die. The best defense is if you’re in it, get out of it. If you’re not, don’t go in it.

Of course, when you’re under attack, there’s nothing that says you can’t send a little back. In fact, it’s expected.

Now granted, we were using blanks, but that didn’t stop the casings from being red hot. I was in the TC seat of the jeep when the shooting started from the woods. My gunner swiveled around and pulled the trigger on the 60. Thunder echoed through the night and a river of hot metal flowed from the gun. It bounced all around the jeep. Some of went down the back of my BDU top and between it and my T-shirt.

The Drill had warned us to have our sleeves down and buttoned. They also warned us to pull the cover material out of our helmets and drape it down our backs. This was to help keep the casings from burning us.

But some still got through. When a spent cartridge went down my shirt, it felt like someone had poured Ben-Gay down my back. Then they were nice enough to cool it down with a blowtorch (slight exaggeration, but not by much).

But this story is about another time.

Fort McClellan was a great place to practice urban assaults. Not too many years before, it had been a bustling base and not just an OSUT site. What’s an OUST post? That’s where we went through Basic and AIT and stayed in the same unit. It’s a cool idea.

One thing the post had going for it was dozens of old warehouses. Every one of them was empty except for rats and the occasional snake. They were perfect for what we were doing.

Until recently (last twenty years), Urban Assault training was almost a lost art. During Big Mistake Number 2, Allied troops in Germany and Italy got plenty of practice clearing buildings. Nam saw little of that. The military has an annoying tendency to train for the last war, and despite the ever-present threat of Soviet aggression into Europe, we did little urban warfare training. I’m sure that counted against us for a while fighting in Iraq.

Today, that has been fixed, and soldiers practice urban warfare religiously. The tactics have been refined and are better than ever.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Today, we were practicing a squad-level assault on a building.

Picture this. You’ve two warehouses that dated back to WWII across from each other. They’re separated by about twenty yards of bare ground with rusted railroad tracks running between them. It was easy to imagine train cars sitting there being loaded with food and munitions bound for some battlefield somewhere.

But today, there was nothing. In a few years, the warehouses would be torn down, and all they were good for now was for training.

Here’s the scenario. We’ve an enemy element in one warehouse. We need to clear them out.

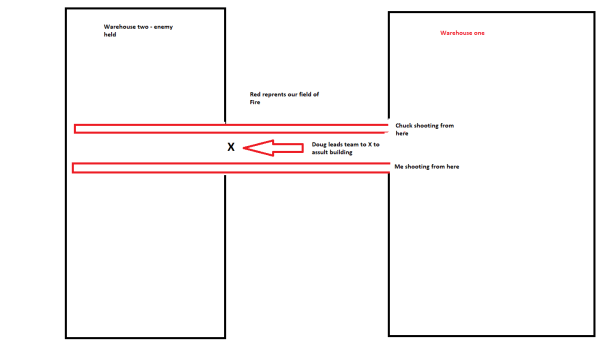

So, we’ve got this large roll-up door directly opposite another door. We have two soldiers, one on each side of the door. Using their M-16s, they lay down a wall of fire between the two buildings. The idea is to keep anyone from coming to the door in the opposite building and shooting back.

An assault team moves up the middle. They get to the objective, crouch down, and toss in a couple of hand grenades. Grenades go off, we lift fire, and a couple of troops roll in spraying and praying with their weapons.

In the real world, it’s a great place for a lot to go wrong in a hurry. For openers, there’s nothing that says you’ll approach unobserved. And there’s nothing to say the enemy wouldn’t toss a grenade of their own out. After all, no plan survives contact with the enemy.

Also, if you’re not paying attention to what you’re doing, your buddy could catch one in the back. Not exactly a nice way to build a friendship that lasts forever.

But this was training, and what could possibly go wrong?

It turns out a lot.

We were set up for the scenario, and this girl we called “Chuck” and I were the ones at the door providing cover fire.

I can’t recall her real name. My Basic/AIT yearbook vanished years ago, so I can’t look it up that way. I pulled KP with her the first week I was at Fort Mac, and that’s where we learned she was a huge fan of Chuck Norris. And that’s where she got her nickname.

I think it was my old friend Doug Mullennax leading the team up the middle. As Chuck and I started laying down fire into the opposite warehouse, the assault team jumped down, and staying low, raced across the open ground between the two buildings.

I heard a cry of pain from Chuck, but she just kept shooting.

“Rich,” she yelled. “You’re spraying me.”

What she meant was the casings my rifle was ejecting were coming down on her.

“Sorry,” I yelled back, still firing. I canted the rifle a little so the rain of hot casings wouldn’t hit her.

Doug got his team across, and they crouched down at the open door. It was a four-man team, and it would involve some serious moving to make things happen. A couple of his team members pulled hand grenades. I could see Doug counting down with his hand. At three, two of the soldiers tossed the grenades in opposite directions into the building.

There was a bang as the simulated grenades went off.

That was our cue. We stopped shooting, and one of Doug’s team jumped and rolled into the building.

The soldier rolled in, came up on one knee and started shooting. No sooner had he made it in than another soldier did the same, only she fired in the opposite direction.

Doug and the other soldiers got in, moved around inside, and I heard him yell, “Clear.”

I looked over at Chuck, and my mouth dropped open. Her left cheek had a burn about the size of a pinky finger on it. It reminded me of a well-done piece of bacon. It was starting to boil up. One of my spent casings had caught her right on the cheek and branded her.

“You OK?” I asked.

I think I was more horrified by her injury than she was. I’d just taken a pretty face and branded it.

If the spent casing had been an inch or two over, it would have gone right into her eye. I didn’t want to think of causing a friend to lose an eye.

Being the tough chick she was, she said, “It stings.”

As if to prove it was nothing, she jumped from the loading door to the ground. She rushed over to join Doug and his team.

If you say so, I thought, following.

The Drills noticed her burn right away. I saw them shaking their heads, no doubt thinking she was fortunate not to have lost an eye. She was sent over to the TMC (Troop Medical Clinic) when we got back to Charlie-10 that evening. Since I made the burn, I got to go with her. She was muttering all how it didn’t hurt.

The next day, she knew all about the burn and complained that it hurt.

I apologized all day long.

The burn looked awful for a week.

We graduated from MP school several weeks later, and she still sported the burn mark. Worse, it showed no signs of going away.

I hope she got it fixed, but knowing her, she wears it to this day like the medals she earned.

Discover more from William R. Ablan, Police Mysteries

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Yes, Rich, hot 50 caliber casings went down the back of my fatigues in Vietnam. It was night, I was inside the APC falling asleep. A trip flare was set off and the gunner started firing. I sat up and raised up to look outside and the hot casings went down the back of my fatigues.

LikeLike

Not a great way to wake up.

LikeLiked by 1 person