One thing I miss about grade school are field trips. They used to take us to some really cool places. For example, the Alamosa Dairy. They had the actual creamery on Main Street in Alamosa and then the dairy about ten miles out where they milked the cows. We got the whole nickel tour and a bottle of cold milk to boot.

Or when we went out to Tom’s potato chips and saw how potato chips were made. We each got a bag of potato chips on that trip. The downside was the chips in my bag were burnt. Maybe that’s what turned me off about buying their chips and I’d eat Clover Club chips for years afterwards.

And we went at least once a year to the Sand Dunes. While it was interesting, it wasn’t one my favorite field trips. Maybe there was some echo from the future that warned me I would spend almost half a year in another sandy place waiting for people to shoot at me.

But the field trip that stuck out in my mind most was the first time we went to Adams State College (now Adams State University).

We got to see a lot of different things on that trip, and it was the first time I got exposed to a form of music I’d grow to love. Our first stop was the Leon Memorial, a concert hall that housed a massive pipe organ. Until I went to Germany and saw some of the instruments in the old cathedrals, this was the largest organ I’d seen. We were ushered in and told to sit and be quiet by our teacher. The organist came out and talked a little about the organ. Then he sat, and launched into some good old fashion Bach (I want to say it was Toccata and Fugue in D minor). I remember the sound hit me in the chest and my insides seemed to vibrate from the sound of the pipe organ.

My classmates called it “Dracula” music. I called it “Fantastic!”

I was a weird kid back then. Come to think of it, I still am.

Then we walked over and got to see the college radio station and finally the planetarium.

We arrived at the planetarium and a man I would later come to know as Dr. Nobel Gantvoort showed us the way in. The lobby of the planetarium was tiny, and it had two display cases. One of the cases contained a spectroscope and if you looked through it, it showed black absorption lines amid the different colors. I was too young to know that the lines were the fingerprints of different elements.

We went up a curving staircase that hugged the inner wall of the building. As we got higher up into the building, the daylight faded away and we walked through a door into the actual planetarium. A metallic device like some gleaming insect of metal and glass was mounted in the center of the room while three rows of couches circled it.

The insect looking thing was a Spitz Star Projector and in later years, it and I would become very familiar with each other.

Soon, one of the assistants at the planetarium came in. He worked at the console for a moment. I saw the outer globe of the Spitz projector cover over with tiny points of light.

Then he started the show. The light faded from the room and overhead scattered across the dome, the stars came out,

It was a show called, “Let’s go North, Let’s go South.” The idea was you were on a spaceship orbiting the earth. The metal insect machine moved and spun, and the stars drifted past an overhead pointer tht was supposed to be our position. As it moved past a constellation, the assistant like a tour guide in Hollywood, told us the stories of the stars.

We sailed past Andromeda, and he thrilled us with the story of the rescue of the beautiful princess Andromeda by Perseus. And then he used his pointer to show a fuzzy patch and told us that was a whole other galaxy that was so far away, the light we saw left it millions of years ago.

Then he pointed out the Big and Little Dipper and told us how to find the pole star. Place your index and middle finger on the two pointer stars then follow the direction the pointers pointed to still you’d covered the sky five times with that space between your fingers. That brought you to Polaris. What interested me was he didn’t just stick with Greek mythology but brought in the stories of the Native Americans.

We sailed past Scorpio and Sagittarius. For a kid already fascinated by the stars, this was totally engrossing. I wished I could just float up and get lost among them.

Years later, I would take an astronomy class and then be invited to be one of the people who ran that console. As a child, I’d looked at the console and been totally intimidated by it. By the time I did what I call my crowning achievement at the Zacheis Planetarium, I could play that thing like Virgil Fox could play the organ.

Observatory at Adams State

I was already thinking multi-media and the best show I did was something called “the Planets.” Pioneers 10 and 11 had just done their flybys of Jupiter, and the results of Mariner 9 were still hot. I got the pictures and made slides of some of their imagery. I also had a National Geographic that had paintings by Don Dixon and others. I cut it up, photographed the images for slides and began putting my show together.

In the past, there had been a screen that a slide projector flashed its images up on. While this was adequate, it didn’t fit my vision.

I wanted my show to have images of the moons and planets on the dome and to happen all around the audience just like it would appear if we were on a spaceship visiting one of these far-off worlds. To pull this off, I borrowed every 35mm projector, cart and drop cord from the library and AV center on campus.

And a since this was my idea of a major show, it demanded a major soundtrack. We were only visiting three worlds and then diving into deep space. That meant selecting music that was epic in structure.

Leaving Earth and Mars – Rick Wakeman’s – Journey to the Centre of the Earth – Movement one – vocals were removed

Jupiter – Joe Scott – A Symphony of our Time – Movement one

Saturn – Debussy – Afternoon of a Faun.

Deep Space – R. Strauss – Death and Transfiguration

Return to Earth – Last movement of Rick Wakeman’s Journey to the center of the Earth – Basically, Hall of the Mountain King. Just a note, but the synthesizer work on this is amazing.

I started the show by inviting the audience to let themselves go and drift up among the stars like I’d wished years before. Only now, we drifted off to Mars and using all the different projectors, we went around Mars, barnstormed known features on its surface like Olympus Mons, and zoomed up to tack past one of its moons.

We did the same with Jupiter and Saturn. Of course, we didn’t know then what we know now, or I’d have spoken about the European icepacks and the potential for an ocean deep down, or what Cassini taught us about the rings of Saturn.

While it was a good effort, it was nothing compared to what they do with planetariums today.

Today, in most cases, the old star projector is gone. In its place is the ultimate computer display screen. While the stars are still there and you can still do an old-style show (here’s the Big Dipper, here’s Orion), what has happened is an immersive entertainment/educational experience. What was a challenge to do years ago then, isn’t as much now.

An example of what I ran into was having Jupiter projected up on the dome. It’s a crescent shape. This means we’re behind Jupiter looking at it and back towards the sun. Human eyes have yet to witness this directly (our probes have, but we get to see what they see second hand). One of the moons moves slowly across the sky. I accomplished that courtesy of a second projector on a mount that allowed me to move the projector without bumps or wiggles (or so went the theory, it didn’t work exactly right without a few shakes).

impressive, I used to make my shows better.

The shakes and wiggles was just part of the issue. The real problem was these were projections, placed up on a dome filled with stars from another projector. It kind of ruined the illusion to have Jupiter, a rather solid object to light with a star in it. You wouldn’t expect to have stars shining through it.

In Hollywood, you’d often times use a Matte to eliminate the background so you can have one solid object pass in front of the other without danger of the background object seeping through. My problem was it’s difficult to use mattes in a live setting. Mattes also leave a hard ring around the foreground object. Think the original Star Trek with the Enterprise coming into orbit around an alien world. there’s often times a black line around the Enterprise.

A matte, or a traveling matte as they’re often called, would have ruined the illusion.

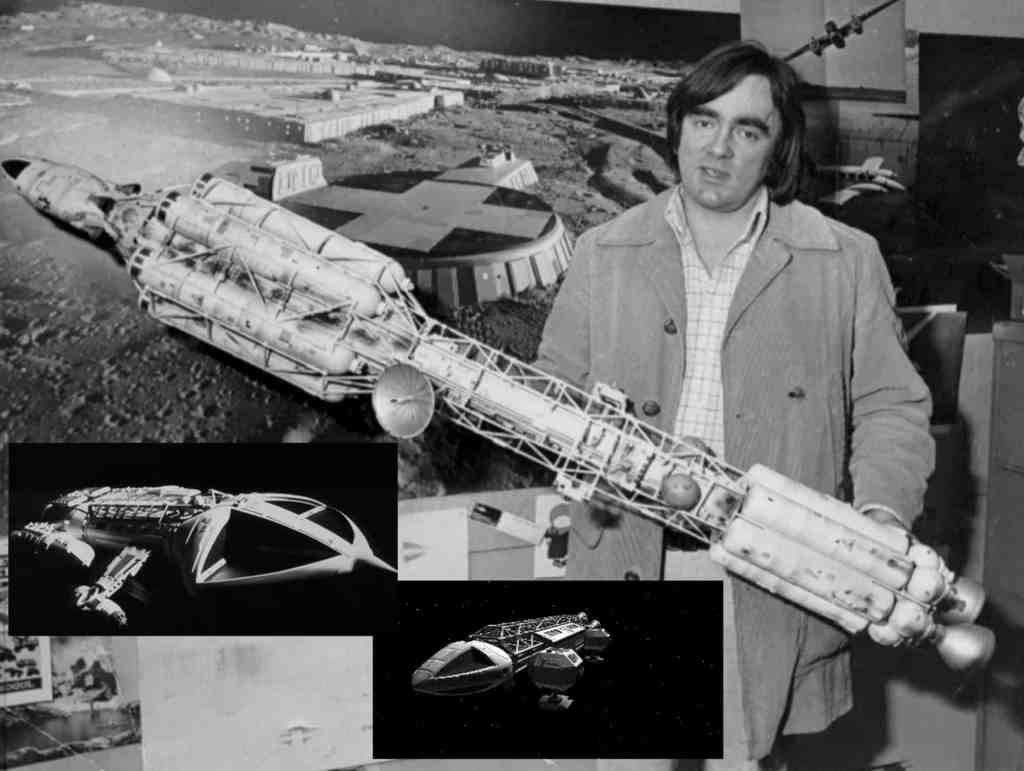

I ended up borrowing a page from what Brian Johnson did with Space: 1999. Often times to have an object moving across the sky, he shot the model and made notes of where it was in the camera field. They then wound the film back and shot the star field, making sure none of the stars were near the track of the model and if they were, that they were very faint. This lowered costs, gave better image quality, but was a lot more labor intensive.

The only way around it for me was to dial down the star brightness and put the image in a patch of sky almost devoid of bright stars. I had to hope, like Johnson and his crew did, that the star(s) would be lost in the image, and no one would notice if something passed through it. Of course, I had to remember to turn the sky up again.

Today, I’d just tell the system to eliminate the stars behind the object.

I did end up making some use of mattes. In some cases, a projection of a planet or moon would have a lighter square around it. This was because of the slide. We had a slide duplicator so what I did was to duplicate the slide, not to color film, but on black and white film. I then mounted that (Since it would be in black and white, the planet would black) and shot it again in black and white. Now the planet came out more or less transparent, and the surrounding area blackened. I then took my duplicated color shot, and cutting the two layers of film to match, mounted them in a slide holder. this got rid of the surrounding background square (more or less). I had to be careful that it wasn’t too thick, or the slide would jam in the projector.

I took my family to a show at the Zacheis Planetarium sometime around 1995. The old projector was still there, and it was fun watching it twirl around and do its thing. But it was kind of odd to be in the audience and not running it. It was a little like being Captain Kirk on the bridge of the Enterprise and not as Captain, but as an invited guest.

Not too many years ago, the Zacheis Planetarium joined the digital revolution. The old Spitz projector is gone, replaced now by the same computer technology many of the larger planetariums use. Stepping foot in there today would be an almost alien experience for me. It would be like returning home and finding someone had gotten rid of all the furniture, torn out walls, and painted everything.

But I still enjoy walking into a planetarium, letting the lights go down, and romp among the stars.

Discover more from William R. Ablan, Police Mysteries

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I took a semester of pipe organ in college. Yes, hits you in your chest, especially Bach. As I read your story, I began to hear Fresh Aire 7 by Mannheim Steamroller, which Chip Davis did with the London Symphony and Cambridge Singers. To the Moon: Lumen, Escape from the Atmosphere, Dancin’ in the Stars, Z-Row Gravity, Creatures of Levania, Earthwise/Return, and the Storm. I may just have to listen to it again and head among the stars (which are already named, in spite of the guy on the radio trying to sell names for them as gifts).

LikeLike

I wonder how much money he’s made off that scheme? Well, I guess a fool and his money are soon separated.

LikeLike