One fine day, the crime scene sketch is going to be a thing of the past. One day, a detective will take their pictures, load them up into a computer that will fold, spindle, and mutilate the Images and what will come out the other side is a full 3d representation of the scene. A jury will be able to step into the scene and a DA or defense attorney will walk around the scene and point out things like where and how the body was lying, where weapons were, blood spatter, the like. On command, it could show measurements, and such will be displayed. They will show you exactly where everything is and how it appeared when detectives showed up.

To a degree, this already possible though it’s still confined to a display screen (may have to wait a few years till we have Star Trek Holodeck technology).

Also, today, we have Crime Scene Technicians to do all the heavy lifting. These are people trained and experienced in crime scene processing and are a huge asset to a department. But here’s the problem. not every department is big enough to have one. In that event, they might appeal to the State Bureau of Investigation for assistance. But like all resources, there’s only so much in terms of resources and limits to what they can provide.

A lot of times, the local investigator will still have to do all the processing and make the sketch. He’ll want to give a jury an idea of how things were laid out and where things were found.

And by taking measurements, it’s possible to reconstruct the scene so everything could be relocated into it within inches. The sketch and measurements would be very handy for a cold case or a scene where the original site no longer exists or has been altered someway (like a remodel).

Event Horizon happens in the mid 1990s. That was the age when home computer technology was beginning to explode. Computers were becoming more and more common in the home and AOL was the up-and-coming titan of something called the Internet. Already, the first drafting programs were showing up, but it would be a little while before specialized stuff like a crime scene sketching programs became commonplace.

So, Will’s department doesn’t have this software yet. Sketches had to be hand drawn.

Invariably there would be two sketches. One would be made at the scene by the detective and would be extremely rough. But it would have the shape of the room or house and sketch in furniture. In it, they’d draw the body (we’re talking murder here) in the approximate location. You’d sketch in where things were found like say a handgun or a pistol casing.

Then you’d have measurements. Like I said, the idea would be to be able to rebuild the crime scene long after the fact. The easiest way to do this is to treat the room like it was graph paper (all my finished sketches were on graph paper). Here’s an example:

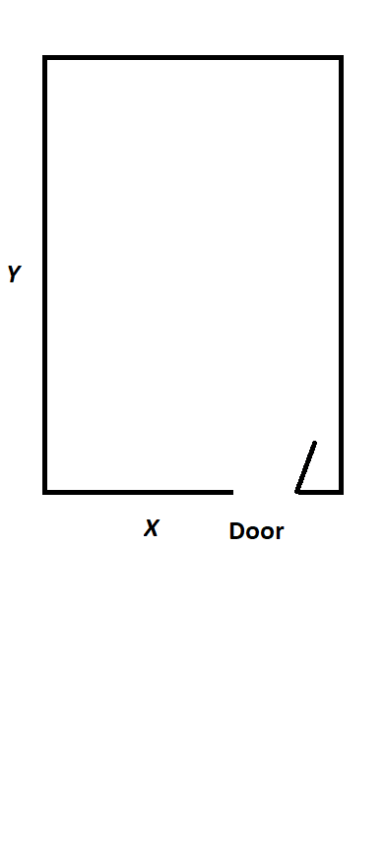

let’s say this is our room. Pretty basic box.

I’ve marked the door and if there was a window, I’d put that in and mark it. I’d do the same with furniture in the room.

Notice that I included an “X-Y axis” like I would have on a graph in math class. It’s along these axis’s that I’ll make my measurements

After I’d photographed everything and before I collected the evidence, I’d want to get my measurements, I’d first establish the values of X and Y (how wide and how long is the room).

In the 1990s, we’d have used a good old fashioned tape measure to establish those values. Now Murphy will always show up and screw up your measurements.

How?

Well, first it’s a huge surprise if a room is “perfectly” square. An example is my office. One X value is defiantly longer (by three inches). Basically, the carpenters were drunk the day they laid out the walls. Also, here’s a surprise. Tape measures may differ a little so expect that. While they shouldn’t differ that much, you might encounter some where they’ll be a difference up to 1/4 inch. Don’t sweat it. We’re doing a sketch where some difference is expected, not planning a mission to Mars where millimeters count.

The other surprise is rooms are lived in so it’s not unusual to try to run a tape measure under or behind a sofa or worse, have to work around a built-in counter.

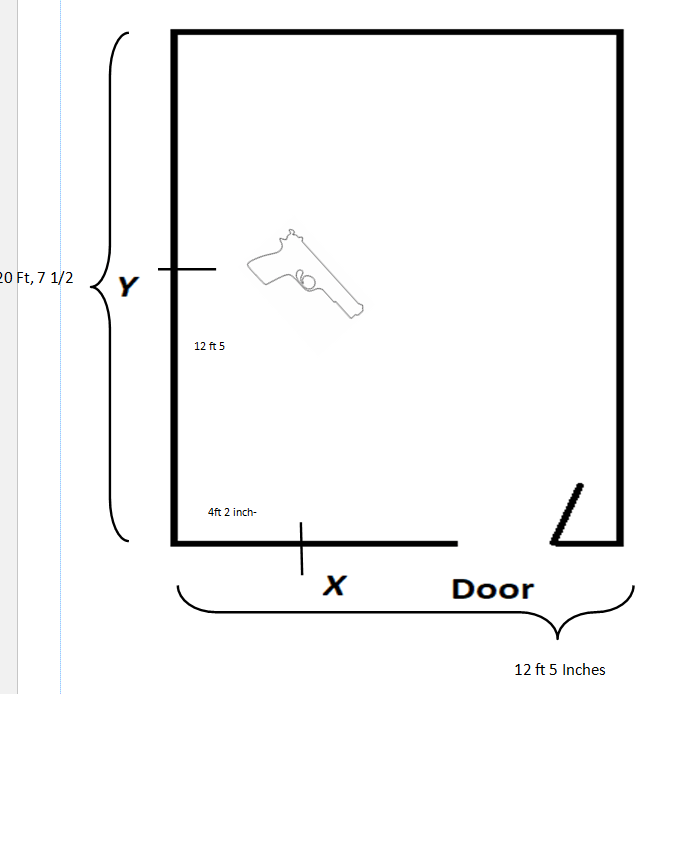

But assume you overcome those difficulties, and I want to establish where a handgun was found at a crime scene.

Here, I’d measure from the corner of the room along my X axis to a point where I was in a 90-degree angle with the object (in this case, a pistol). I’d mark that location on my sketch and enter in the distance covered. A carpenter square or protractor fixed to a piece of wood and with a long string is a handy DIY tool to determine if you’re actually 80 degrees from wall to object.

I’d do the exact same thing with the Y axis.

Then, if you go to those locations after the evidence has been removed, shoot 90-degree lines from that distance on the wall, out, and where the lines intersect is where the object was. If you did your job right, you’ll be within an inch or so.

The measurements aren’t like anything a surveyor might field. Most detectives wouldn’t have a clue on how to sue a transit, but this technology has been around for centuries, and it works.

Now, here’s where people get in trouble. If I made a rough sketch of a crime scene and I put it in my notebook, my notebook could be requested as evidence. Whatever you wrote in the book has to be the same as you put on the finished sketch. and it has to be legible.

Want to feel like an idiot? Have an attorney look at your report and ask, “What does this word say?”

Now the question becomes, why couldn’t I do a finished drawing at the scene. I could and more than once the sketch I made in the field became the finished sketch. But if I’m using templates like the one above, I might wait till I got back to the office. A good set costs money, and I tend to misplace things. Besides, sometimes you’re making sketches in adverse conditions (processing a scene in the freezing cold room isn’t much fun). I might make a rough sketch, get my measurements, and then clean it up later by doing a finished sketch.

Now, a place where this falls apart if you’re not careful is outside. A crime scene can be spread out over several acres. In Life on Mars, Will and RJ use utility poles as fixed points to measure from. Utility poles, if you never noticed, are numbered. Each number is unique. The electrical or telephone company has them plotted on a map. Even if the pole is replaced, the old map is kept so it becomes a known reference point. Using three known points they did something similar to what was done in the room and set up a rough grid system to measure from (I didn’t describe the process in the book. But that’s how we’d have done it in the real world).

A modern-day tool that has been used to great advantage by detectives is a laser tape measure. This is the same device the carpet installer uses to give you an estimate and they are very accurate. I’ve never used one at a crime scene, but I can easily see how useful they might be.

One that might have been very difficult for RJ is the Brightman case. Modern technology saved the day there.

The Brightman case is one of those cases that threads itself through several novels. It begins in the very first novel and isn’t resolved till the fifth. Mr., Brightman is old and dying of cancer. This was supposed to be his last hunting trip (it was). He and his sons are in the mountains during hunting season when a brutal winter storm comes in. Since he is unable to hike out, his sons leave promising to return with horses. By the time they got to where they could get help, the storm was so bad and so much snow accumulated that, even horses couldn’t get through.

After several aborted attempts, rescuers led by then Deputy RJ Madril, at last reached the camp site to find that Brightman is gone. It’s assumed he panicked, tried to get out on his own, and perished in the storm.

Almost two years later, his remains are found, but they’re scattered over several hundred yards of forest. The problems here is there are no reference points. You can’t use that big tree (unless the forest service marked it for some reason) because all trees look alike.

To help locate our crime scene on a map in this situation, we could have done it the old school way. Using a topographical map, I’d have pulled out the old lensatic compass like we used in the military, shot a couple of azimuths, and then plotted my location on the map. Not exactly the most accurate way, but on the other hand it works well enough to call in airstrikes and artillery rounds.

Or I could have looked at the map and just eyeballed it. Not the best way, but it works if close is good enough.

RJ has a high-tech tool at his disposal and that’s GPS. He establishes three points using the GPS and marks each with a stake. He then runs twine between the points and instant grid system. He could have also simply mapped each bone and fragment of clothing using the GPS.

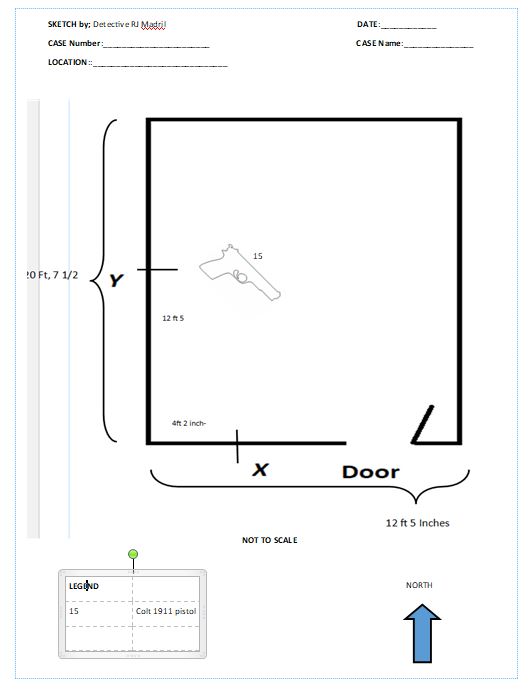

Whichever method is used, the finished sketch will have a lot of information on it to include the name of the detective, a case number, date, what this is (crime scene sketch of . . .), location (address, grid coordinates, whatever) and a legend if possible. You should also have a north arrow.

At the bottom of every one of my sketches, not matter how accurate it was, I always included the words “Not to scale.” Murphy also dictates that someplace, somewhere, some defense attorney will nitpick some little thing to death.

That’s their job you know.

FILE DOWNLOAD – HOW TO USE A LENSATIC COMPASS – USMC manual

VIDEO on finding your location on a map using triangulation: Click Here.

Discover more from William R. Ablan, Police Mysteries

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.