NOTE: I’m going to be dead honest here. This post was hard to write, and it points out something you’ll hear again and again (and not just from me). You might get past it, but you never forget it. The other is what I consider a dying art, and that’s the art of “listening.” And I’ll talk a little about what happens when someone isn’t listened to. Indeed, I’m not sure what hurt most, the incident or not having anyone listen. And a quick apology. The first part of this is a little graphic. Apologies. – Rich

__________________________________

“My L.T. and I were looking at some tanks that had been hit,” I said. “I’d seen one like these at NTC. I’m telling him about it when I noticed he was looking at the ground. I looked to see what he was looking at and saw a glove.”

We were sitting at the kitchen table. I had a cup of coffee in front of me. We were looking at a picture of me standing in front of blasted to hell Iraqi tank.

“A stream of ants was going in and out of it,” I went on. “I wondered why and then I noticed the glove wasn’t flat. There was something in it. I took a step back when I realized why the ants were there. They were taking away a piece at a time, what was left of someone’s hand.”

My folks didn’t say anything at first and when they did, they asked, “Are you going to be able to take the cows to the mountains with us?”

It would be a very long time before I spoke of it again.

My story isn’t too far off from one a lot of veterans have experienced. We finally feel safe enough to say something only to have what we’re saying shutdown.

The question becomes, why such a reaction?

Perhaps one of the single biggest reasons is that some of the stuff we witness, much less have to do, is so far outside the norm that people can’t relate. That’s OK. They don’t have to. All they need to do is listen. No judgment. No changing the subject. No trying to fix it. Just listen.

Listening is the single best thing you can do for anyone displaying signs of PTSD. You might not have been there. You might not have seen what they’ve seen. But feeling safe to discuss is a biggie. And don’t expect it to happen overnight.

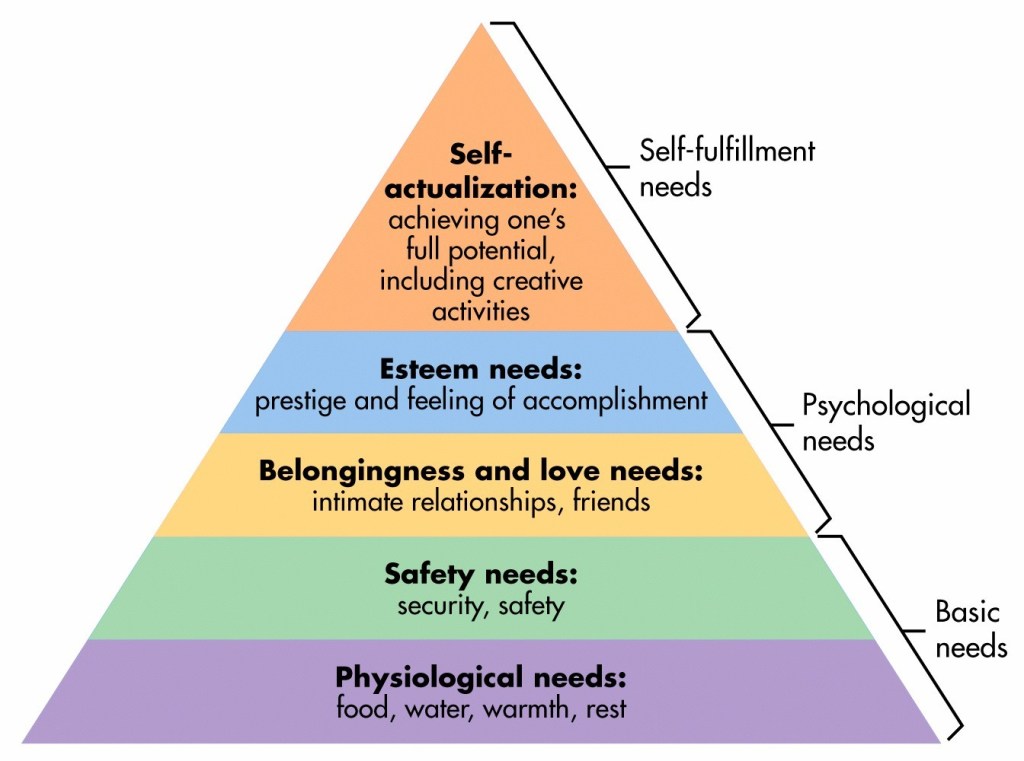

In his book, Headspace and Timing, Duane France speaks of something every Psychology 101 student has head of. It’s called Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Before a sufferer feels safe enough to discuss whatever they need to talk about, there’s a lot of things that have to happen first.

Top of the list (or in this case, bottom of the pyramid) is basic stuff. Food, Shelter, Rest. Sounds easy, but a lot of vets have gone from Mom and Dad who provided that, to the Military which is very good at filling almost every piece of the pyramid. I had an advantage over a lot of my peers in that I’d been a civilian having to get those on my own long before I was a soldier. I had the wiring in place so to speak, while many of them didn’t.

Each step is important before you can talk about it. After all, if you’re just trying to find enough food to eat, dealing with bad dreams is something you’re probably not going to do.

Safety and Security is the second on the list. While we can make the argument that basic housing is a physiological need, the same can be said for Security and Safety. Having a place to keep you dry and provide a barrier against the world is a must. The same is true of the environment around you. You’ve got to feel like you’re free from attack, condemnation, shunning, whatever. If you’re the homeless guy with a sign and you get more dirty looks than handouts, you’re not going to feel very safe or secure in your surroundings, and you’re less likely to talk about it.

Third is psychological needs, and I think this where a lot of PTSD sufferers get in trouble. It’s also where the real work is done. If these aren’t being met, the sufferer will do one two things. They’ll get stuck there and be unable to move on or achieve their full potential.

Or possibly worse, look to fulfill these needs elsewhere. Either they push away and/or drift into behaviors (substance abuse, homelessness, and etc.) that aren’t desirable.

It’s not the sufferer’s fault. We all carry around snapshots of people in our heads and when we encounter them again maybe years later, we’re astonished at how much they’ve changed. Trouble is, we sometimes try to force them to fit the snapshot. That’s especially true of military members. In most cases they go off as young men and women, go through the transforming process, and even if they never see combat, they come back a different person.

Since the person no longer fits that snapshot, we might try to push them into it. That means the sufferer might find themselves judged, ignored, and left not feeling important. Relationships is the name of the game and none of that builds good relationships.

It’s important to realize this young man or woman isn’t the person you knew. They’ve grown. They’ve experienced hurt. They’ve gone places and done things you haven’t. That person is gone and will never be back. Don’t force it.

Likewise, the returning vet needs to realize the people left behind haven’t changed that much.

I talked a little about that in my second novel, Life on Mars. I call it that because Will is comparing his life to a story by Ray Bradbury. In that story, astronauts land on Mars, open the hatch, and their hometowns are waiting for them. They encounter a world just familiar enough to be home, but just alien enough not to be.

Will says he’s in a world just familiar enough to be home, but one he doesn’t know.

Moving on.

Judgment can happen without even saying anything. The look on your face tells the person who’s relating the incident to you all they need to know. This is too (INSERT WHATEVER HERE) for this person. It also reinforces the idea that whatever we witnessed is too much for someone who hasn’t been there or done that. They’ll judge me so why talk.

Or worse, I’ll try to protect them from it and so we don’t talk about it. As a result, we begin to think the only ones who would understand are the ones who have been there. Problem there is that you’re dealing with hurting people as well. Sometimes it works because there’s no judgement. And since they’re been there, they’re smart enough to just listen. That doesn’t always work because sometimes this happens over a beer and you’re not dealing with getting better, but bleeding into each other’s wounds.

A small aside here. The worst possible thing you can tell someone suffering from PTSD is “The (whatever) is over. Get over it.” They know that and that’s what they’re trying to do. You can’t fix it. The sufferer has to and the talking process is part of “getting over it.” But they have to do it at their speed, not yours. By telling them to “Get over it,” you’re telling them this conversation isn’t worth having.

Listen to what is said. A simple nod of the head or an “uh-huh” can blow the dam wide open. Just listen.

It doesn’t matter if you spent thirty years in the military or never once darkened the door of recruiter’s office, the idea is to be there and to listen. I’ve a friend who’s very good at this. He and I couldn’t be more different, yet he has more understanding of me than most because he listens.

_______________________________________________________

When it’s time to deal with it, it’s time. And since I’d been shut down, I wouldn’t. So, I played it over and over, and the more I dwelt on it, the more the incident took on epic proportions in my life. Seeing a glove like the one I’d seen or an abandoned glove on the ground would bring it back again. I found myself wondering about the person who had owned that hand. Did that hand hold the hand of someone he loved? Did it caress the face of a child. What was it like to lose it?

Eventually, my imagination filled in the blanks, and I began to dream about it. Most of the time, I was replaying the incident over and over in my mind. Sometimes, in my dreams, I’d see a guy stumbling around looking for his missing hand. In one very horrifying nightmare, I was the guy who lost the hand. My tank has been hit, I’m scrambling out of this burning hunk of metal, when another hit blows my hand off. Without the hand, I can’t get out and my clothing is starting to burn.

I’d wake up with a scream on my lips, the blankets wrapped around me in a ball and drenched with sweat.

My wife, Julie, would ask what was wrong and I wouldn’t talk to her about it. After all, what was she going to say. “It’s just a dream?” I didn’t need to hear that.

And so, I never talked about the glove. At least not for a while. And having seen how my parents reacted, I didn’t know if I could stand that reaction from her. So, I never told her. And so, I wouldn’t, I began shutting her out.

The shutting out was something I didn’t realize I was doing. On some subconscious level, I was deliberately sabotaging my relationship. In the book, Headspace and Timing, Duane France calls it tossing grenades into your relationship. I think I was a little short of nuke strike. After all, why get close to someone only to have them not listen.

One day, I was out chopping wood. Winter was over, but in the San Luis Valley, the next winter is already on its way. I had a few months to chop up enough wood to keep us warm during it.

Julie brought a large glass of iced water out to me and sat down on a log.

“Baby,” she said. “We need to talk.”

No good conversation ever started that way, I thought as I took a sip of water and sat down on another log. “What’s up.”

Years later, I would make the comment that I was tough guy and I needed a woman who could keep up. She proved she was just as tough as me when she put the cards on the table. “Something’s going on with you. You’re pushing away from everyone and you’re having terrible dreams.”

I couldn’t deny it.

“You need to talk to someone about this,” she said.

“You mean like a psychologist?”

My first thought was to eighty-six that idea. Despite having taken a lot of psychology classes in college and knowing how counseling worked, there was still that piece in me that said, “Only crazy people go to shrinks.”

This would be amplified a few days later when I told my folks I was going in. “Don’t do it,” was their counsel. “They’ll label you crazy and you’ll never get a decent job again.”

Thank God I didn’t listen to them. I’ve always thought that was strange. If you had chest pains, the first thing people would say is get to a doctor. But if you’re having issues in life, they tell you to hide it even more.

Funny! And I don’t mean funny ha-ha. It’s funny strange.

But now here was someone I loved, felt safe around, and who knew the score, telling me I needed some help. It was done with love and compassion. But she told me what the stakes were. “If we’re to have a future, you need to talk about this. You’re kind of stuck there. And till you talk about it, you’ll stay stuck. And eventually, you’ll push me right out of your life.”

She knew where I was headed.

I nodded. “Aren’t you a counselor?” I asked.

“I am,” she said. “Trouble is you and I are in a relationship. You might hold back thinking you’re protecting me somehow or that I might think differently about you. No. It needs to be a neutral third party.”

Two days later, I was sitting with Joseph at the SLV Mental Health Center.

It was one of the best things that ever happened.

NEXT : PTSD – Part 4 – CREATING THAT SAFE ZONE

Discover more from William R. Ablan, Police Mysteries

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

How I appreciate your honesty.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Joy. This one was hard.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I got that feeling. That you shared details is a good thing for the rest of us, who don’t know what to say.

LikeLiked by 1 person