Before diving too deeply into the history of PTSD there’s a couple of things I want to SHOUT out at you on the subject:

-PTSD CAN HAPPEN TO ANYONE, and

-IT’S NOTHING NEW. WE’RE JUST FINALLY GETTING A HANDLE ON WHAT IT IS AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT.

PTSD stands for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. That’s nice. So what is it?

PTSD is defined as a Mental and Behavioral disorder that develops from experiencing a traumatic event such as sexual assaults, warfare, traffic accidents, child abuse, spousal abuse, domestic violence, and civil violence.

It can be associated with something called a Traumatic Brain Injury, basically a good old concussion. This can be the result of an explosion (say in combat), a car wreck, being struck hard (such as in football or boxing) or even a simple fall at home. If you ever have an injury that results in being knocked out, headaches, nausea, or such, GET HELP.

The key words here is traumatic events. And since we all stand a chance to be part of some traumatic event, we can all suffer PTSD. So, it’s not just confined to military personnel or First Responders. IT CAN HAPPEN TO ANYONE regardless of age, gender, background, education and so on.

This is just a brief and by no means all-inclusive list of some of the symptoms. They can include disturbing thoughts or feelings, recurring dreams of the event, mental and physical distress caused by sensory cues, and increased violence and/or increased fight or flight responses. In the novel that I’m working on (Waiting for Planes that Never Land), we’ll see most of it.

It can cause all manner of interesting behaviors or illnesses. Depression is a big one, substance abuse, even hallucinations, separation from society, physical illnesses, and even suicide. That said, it’s not something to be taken lightly.

The single most important thing about PTSD is IF YOU’VE EXPERIENCED A TRAUMATIC EVENT AND EXPERIENCE ANY OF THE SYMPTOMS, GET HELP. You will hear that again and again throughout this series.

Now, to the history of it.

PTSD has no doubt been with humans ever since the model came out. Looking through writings, we see the symptoms mentioned in Homer’s Iliad. Wild Bill Shakespeare touches on it in Henry IV, as did Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities.

While the Bible doesn’t address it by name, it’s a safe bet that some of the writers had it. Going through the Psalms and seeing what David wrote, it’s obvious he had a streak of PTSD a hundred miles wide. Despite his greatness and his willingness to lean on God, it still bothered him or at least impacted him in some ways. One could argue that some of his worst mistakes (his affair with Bathsheba and some of his worst battlefield decisions might have had roots in it).

So, it’s nothing new.

in 1761, an Austrian doctor named Josef Leopold wrote about what he called “Nostalgia” among soldiers involved in military trauma. Some of these symptoms were depression, sleep disorders, and extreme anxiety. Many reported missing home. When asked why, the answer was simple. It’s safe at home.

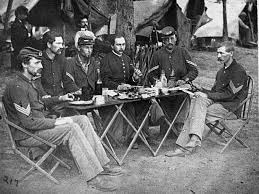

The American experience with PTSD and an attempt to get a handle on it begins with the Civil War. The doctors of the time understood something was going on but attempts to define it were compromised because the study was new. Also, they didn’t have the technology to see the brain and the subject of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI – a big issue today among our vets) was something that could be conjectured but not treated easily. They were seeing some of the same stuff Josef had discussed but were having issues putting a finger on the cause.

About the same time, studies came out of Europe that showed similar reactions among civilians involved in rail or shipping accidents.

The thought that at least some of the symptoms could be caused by physical injury surfaced when Jacob Mendez da Costa, a US doctor, did a study of Civil War soldiers. It showed rapid pulse, anxiety, and breathing trouble. It as called by several titles to include “Soldiers Heart,” “Irritable heart,” or “Da Costa’s Syndrome.” It was described as an over stimulation of the hearts nervous system and often treated with medications to help control symptoms.

The thought that physical injury could lead to PTSD-like symptoms was also supported by studies form Europe of what they called “Railway Spine.” Since rail travel in Europe was more common by train then it was in the States at the time, there were more accidents. Autopsies on victims showed damage to the central nervous system and the brain. We see the same thing today among auto or air accident victims. Assuming they survive, there can be injury to the brain resulting in behavioral changes.

A historical note here is that author Charles Dickens (A Christmas Carol, Oliver Twist, Tale of Two Cities) was involved in a rail accident in 1865 and wrote of not being able to sleep or even experiencing deep anxiety when hearing or seeing trains.

And that’s where it stayed until World War One.

It was in WW I that doctors first began connecting the dots between PTSD and TBI, but it was called by a name that came to be disparaged. They called it “Shell Shock’ and it was thought to be caused by the close explosion of high explosive ordnance. While some of it was certainly that, it was also noted among soldiers that were nowhere near explosions. Some realized that they were dealing with two different things that may or may not be connected. Those that hadn’t experienced nearby explosion were labeled with what they called “War Neuroses” or later “Battle fatigue.”

The treatments were varied. Soldiers might receive a few days rest before being tossed back into the fray. Chronic cases focused on daily activities to increase their functionality to return them to productive civilian lives. European hospitals used hydrotherapy, electrotherapy (think primitive electro-shock) and hypnosis as therapies.

World War Two saw the first real advances in treating it. The “Shell Shock” term was replaced with something called CSR (Combat Stress Reaction) though Shell Shock was still in use. The human body and mind can take only so much and soldiers, many of whom had been fighting for months or even years, became weary and exhausted. This was when the term “Battle Fatigue” surfaced.

Not all combat leaders accepted it as a real thing. It’s common knowledge that General George Patton slapped down a soldier (actually, it happened more than once) because he supposedly had combat fatigue. George didn’t believe it existed. Interestingly, George himself might have suffered from a series of Traumatic Brain Injuries which could account for some of his behavior. While a young man and stationed at Ft. Riley, Kansas, he was thrown from a horse, landing headfirst. George is reputed to have always had a bit of a temper before, but people who knew him said that his temper was even worse after that! And that wasn’t the only fall. In one rather dramatic instance, he is reputed to have taken a fall, and a few days later, while sailing his yacht, looks at his wife in confusion and asks how they got there. He was unable to account for the time between that moment and the fall. We can only speculate on how the falls and concussions impacted his personality.

One thing is certain, combat fatigue could be blamed on a high number of military discharges during the war, and it became expedient to find ways of treating it. Soldiers with CSR was treated using the PIE approach. PIE stands for Proximity, Immediacy, and Expectancy. Fans of the TV show M*A*S*H* may be familiar with Dr. Sydney Freedman, an Army psychiatrist played so well by Alan Arbus. In several episodes, he’s heard to say that treatment needed to start right away, and to get the soldier back to their unit least a problem become a lifetime issue. The patient had it reinforced on them that they would get better. Being back with their friends and peers helped in the treatment since there was a support group for the soldier. That was a first-class example of PIE.

In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association produced what’s known at the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders which included a catch all diagnosis of “Gross Stress Reaction.” Interestingly, it applied only to people involved in combat and/or a disaster. It was felt this was dealt with quickly by the human mind and if it persisted after 6 months, then some other treatment was needed.

When the second version came in 1968, the term was dropped and the only reference to anything even looking like PTSD was trauma caused by an unwanted pregnancy with thoughts of suicide, fear linked to military combat, or something called Granser syndrome (marked by incorrect answers to questions) in prisoners facing a death sentence.

It wasn’t until the third version in 1980 that the term PTSD was actually used. This is the first time it came up on my radar and I recall reading about it in Police magazine. I’d suffered my first serious assault on my person as a rookie officer and after reading the article, I recognized some of the noted reactions to me. Of course, I didn’t get help. If you’ve ever taken a psychology class in college, you’re probably familiar with the prof laying out symptoms of something and you’re sitting there going, “Dear God. That’s me!” I blew it off thinking that’s what it was and ignored it till I couldn’t anymore.

In the article, it mentioned the ‘Nam vet, Holocaust survivors, victims of sexual assault, spousal abuse, and First Responders and others. I saw that behavior in a young man in the community that most considered a burn out and troublemaker. Since it had happened in ‘Nam, I did my best to treat him with infinite respect and to listen to him.

Of course, when you’ve got it yourself and you’re unwilling to deal with it, it’s a little like the blind leading the blind.

Versions three, four, and five, reflected lessons learned. We went from experiencing symptoms for six month or more to experiencing them for at least a month and causing significant distress and interference with day-to-day functioning.

Research shows that it’s common and that people react or live with it in different ways. It also states something I find odd. According to the latest version 10% (10 in 100) of all women suffer from some form of PTSD while only 4% (4 in 100) men suffer from it.

I found that an odd statistic and wonder if it’s a false number. I don’t mean that they’re trying to demean women or lie about their findings. Nor am I saying men are stronger than women. What I’m saying is that we still live a culture where we’re taught that Big Boys don’t cry. Would a guy be more willing to talk about it than a woman?

I think it’s a number that needs to be studied some more.

NEXT: Part 3 – PTSD – Why Talk about it? No one listens?

Discover more from William R. Ablan, Police Mysteries

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Excellent post. Very thorough and right on. BTW, I share your perspective on the male/female stats. Women will seek help sooner than men, and I believe that’s the reason the stats are skewed. I worked with Marine vets who served in the Middle East. Almost all had PTSD, but most of them never spoke about it or sought help. Thank you for posting this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s why I push guys to talk about it. In this novel, my central character (a thinly disguised me) talks about at least one thing he knows was impacted because he didn’t address it, and that’s relationships. Little things like keeping distance between him and people around him, only spending a few years at a job before moving on. It can impact you in places you don’t even think about.

LikeLiked by 1 person